10 Bizarre Medieval Recipes That Reveal What Our Ancestors Ate

Medieval dining was about more than nourishment. Food signaled wealth, faith, and imagination, with recipes designed to shock, delight, or impress. Manuscripts and early printed cookbooks reveal dishes that ranged from clever illusions to unsettling protein choices. While some foods survive in modern form, others now seem strange or even unthinkable. These recipes show how creativity, symbolism, and display mattered as much as taste at the medieval table. Here are ten unusual dishes that highlight the era’s curious approach to cooking.

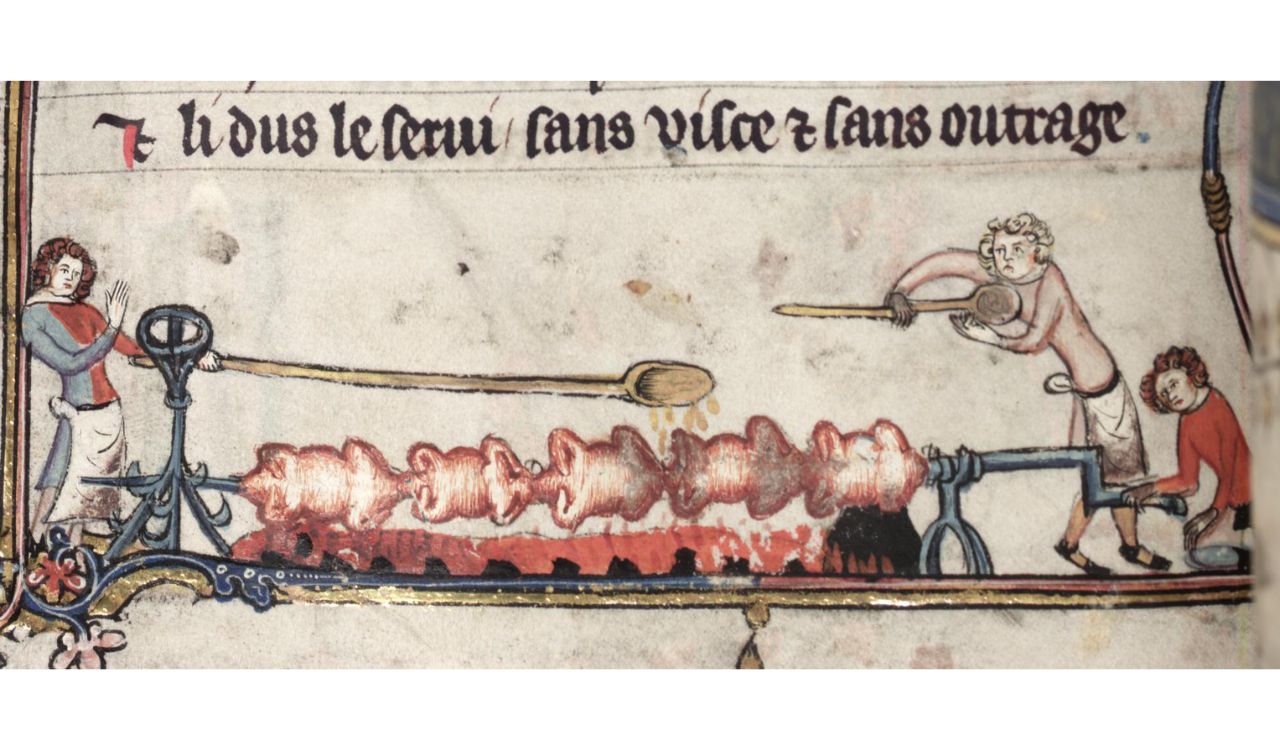

1. Cockentrice

The cockentrice was a feast centerpiece that fused two animals into one. Cooks stitched together the front of a piglet with the back of a capon, or the reverse, then roasted the creation until golden. Sometimes it was brushed with an egg-based glaze to glisten under candlelight. More than food, it was a spectacle designed to amaze guests and emphasize the host’s wealth and ingenuity. The cockentrice survives in late medieval English manuscripts, where its detailed instructions reveal the mix of playfulness and prestige that defined noble banquets.

2. Peacock served in its plumage

One of the most spectacular banquet dishes was roast peacock presented with its skin and feathers replaced after cooking. Recipes describe how the bird’s skin was carefully removed before roasting, then sewn back on with its feathers arranged and gilded. The head and comb were sometimes painted with gold leaf for even greater display. This practice spread across Europe’s courts, where serving the bird in its resplendent plumage signaled grandeur and extravagance. While diners eventually ate the meat, the main purpose was the visual impact when the peacock appeared at table.

3. A pie that releases live birds

The famous story of “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie” reflects an actual culinary trick. A sixteenth-century cookbook included instructions for baking a hollow pie shell, then inserting live birds through a hidden opening before serving. When the crust was cut, the birds would fly out, astonishing guests. This was not a common household recipe but a dramatic form of entertainment for banquets. It showcased the cook’s skill and the host’s ability to provide spectacle, turning dinner into theater as much as nourishment.

4. Pynade

Not all unusual medieval recipes were savory. Pynade, a confection found in fifteenth-century English cookbooks, was made by simmering pine nuts with honey or sugar until the mixture thickened, then pressing and cutting it into small blocks. Sometimes rosewater or spices were added for fragrance and flavor. In an era when sugar was expensive, such sweets signaled luxury and were reserved for high-status occasions. Though simple compared to elaborate meat displays, Pynade demonstrates how medieval cooks used scarce ingredients to create indulgent treats for feast tables.

5. Poume d’Oranges

Medieval cooks loved to trick the eye, and Poume d’Oranges exemplifies that tradition. Ground pork was mixed with saffron and spices, shaped into small balls, and then colored to resemble oranges. Some versions even had a filling or were glossed with a shiny coating to mimic real fruit skin. Served on a platter among actual citrus, these “oranges” delighted and fooled diners. Recipes survive in English manuscripts, showing that such illusions were part of banquet entertainment, designed to surprise guests while demonstrating the cook’s creativity and the host’s wealth.

6. Frumenty

Frumenty was a porridge of cracked wheat, milk, or almond milk, often enriched with eggs and saffron. It usually accompanied venison, but some manuscripts record pairings with porpoise during religious fasts, since sea mammals were classified as “fish.” The dish thus combined a staple grain with a prestigious Lenten protein. Its texture was thick and hearty, making it a filling dish that bridged the gap between everyday sustenance and feast-day indulgence. While porpoise has long disappeared from Western menus, frumenty remained popular in England for centuries afterward.

7. Tansy

Tansy was a bright green dish made by mixing eggs with herbs, spinach, and sometimes the bitter herb tansy, then frying it into a flat omelet or baked custard. Sugar and spices were often added, balancing the bitterness with sweetness. Associated with spring and Easter, tansy symbolized renewal and seasonal change. Its vivid color made it striking at the table, while its mixture of flavors reflected medieval tastes for combining sweet and savory. Although tansy leaves are rarely used today, the dish demonstrates how symbolism and seasonality shaped menus.

8. Umble Pie

Derived from the Old French word for a deer’s entrails, umble pie was made from offal such as liver and heart, seasoned and baked in pastry. It was common in hunting cultures, where nothing from a stag was wasted. Over time, the phrase “umble pie” shifted into the modern idiom meaning humility, though originally it was simply a descriptive term for a venison dish. While not as visually dramatic as a gilded peacock, umble pie reveals the resourcefulness of medieval cooks and their willingness to use every part of an animal.

9. Roast cat

A rare and unsettling recipe appears in Robert de Nola’s sixteenth-century Catalan cookbook, which includes directions for preparing roast cat. The instructions called for skinning a fat cat, discarding the head, briefly burying the carcass, and then roasting it on a spit. Historians stress that this was not a widespread practice but a documented survival of extreme culinary traditions. Its presence in the cookbook highlights how medieval texts sometimes recorded unusual or marginal foods, offering insight into a world where protein sources and attitudes to animals differed from today.

10. Leach

Leach, sometimes written as leech or leche, was a popular sweet in the Middle Ages. It was a firm, jelly-like confection made from sugar mixed with flavorings such as almonds, dried fruit, citrus peel, or rose water. Cooks often added warming spices like ginger, cinnamon, or anise, and used thickeners such as isinglass or gum arabic to help it set. The result was sliced into decorative shapes, served at banquets on silver trays, and even favored by Queen Elizabeth I.