The Real Reason Corned Beef Isn’t Made with Corn

When you hear “corned beef,” you might picture beef mixed with corn kernels or flavored with sweet maize. The truth is far more interesting. The term has nothing to do with the yellow grain that fills summer fields. Instead, the name “corned” comes from an Old English word referring to large grains or particles of salt used in preserving meat.

This centuries-old preservation method helped beef last through long voyages and harsh winters, making it a vital part of food history. Today, the dish appears on deli sandwiches and St. Patrick’s Day tables around the world. But to understand why corned beef is not made with corn, we need to look back at how it got its name, how it was made, and how it became a cultural icon.

What “Corned” Really Means

The term “corned” does not refer to corn as we know it today. Instead, it describes the curing process that uses large grains of salt, historically called “corns” of salt. These salt crystals were about the size of corn kernels, which led to the term “corned.”

The phrase dates back to the 17th century when British merchants used it to describe beef preserved with coarse salt. One of the earliest written references appeared around 1621, describing meat “corned” with large salt grains to extend its shelf life before refrigeration existed.

In this context, “corn” simply meant “small hard particle” or “grain.” Over time, that linguistic detail was lost, leaving modern eaters to assume the dish involved actual corn.

How Corned Beef Was Made and Named

The Early Preservation Method

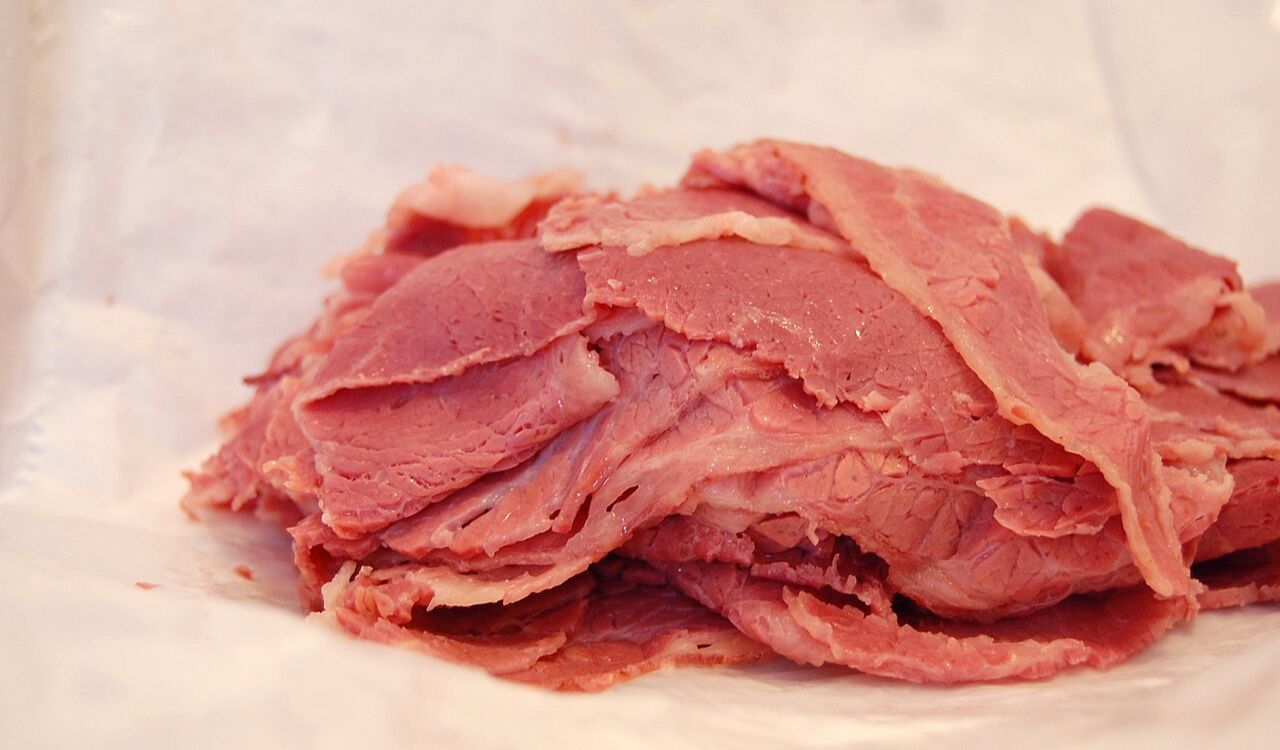

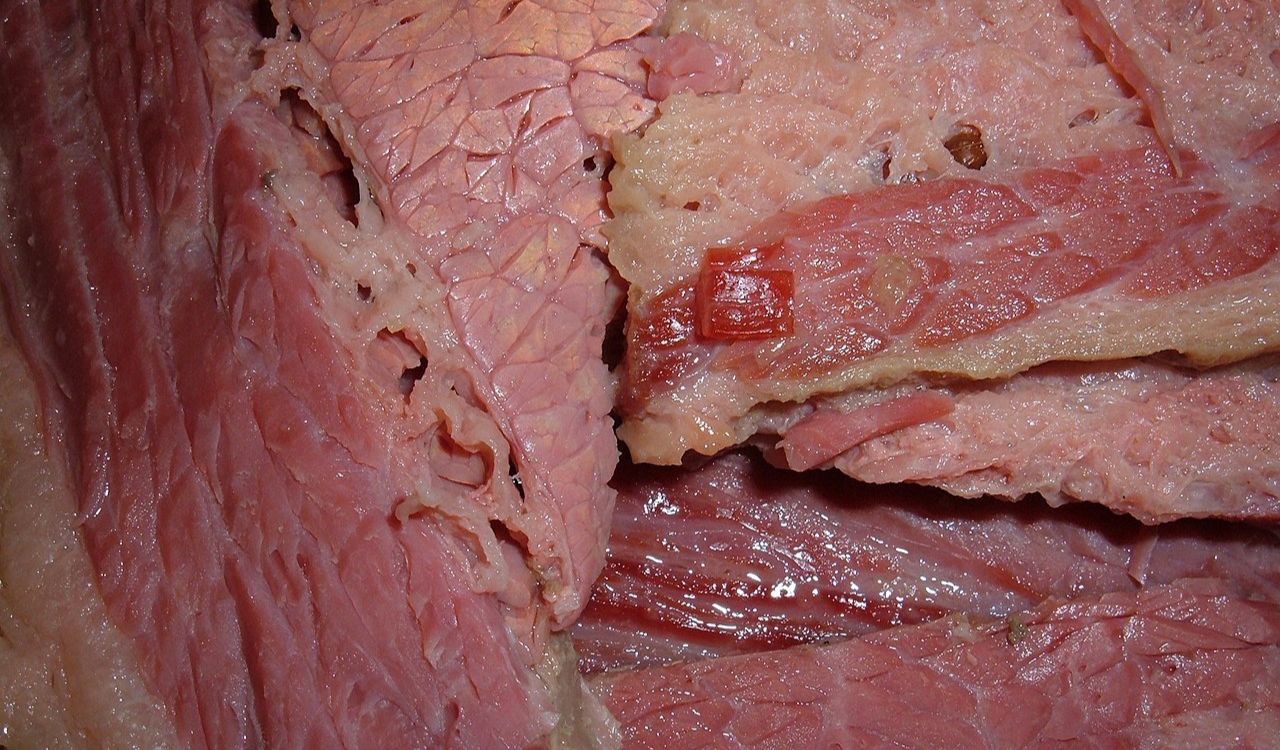

The traditional process for making corned beef involved soaking a tough cut of meat, often brisket, in a heavy brine made with salt, nitrates, and spices. This process cured the meat, helped it stay fresh longer, and gave it a tender texture when cooked slowly.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Ireland became a key exporter of corned beef. Irish producers had access to inexpensive salt, which made them major suppliers for British markets. The meat was packed into barrels with coarse salt and shipped abroad, often to feed navies and colonies.

Why the Name Stuck

The name “corned beef” endured because the process relied on visible grains of salt that resembled corn kernels. Even after industrial refrigeration replaced salt curing, the term continued to be used for cured beef.

As curing techniques improved, finer salt replaced large crystals, yet the historical name remained. Modern corned beef is usually prepared by soaking brisket in a flavored brine rather than packing it with dry salt. The result tastes similar but reflects a more refined process.

The Global Journey of Corned Beef

Corned beef eventually traveled far beyond its Irish and British origins. In the United States, Irish immigrants found beef more affordable than pork and adopted corned beef as a substitute for traditional bacon and cabbage dishes. This adaptation became an Irish-American classic served every St. Patrick’s Day.

In the 20th century, canned corned beef gained popularity worldwide. Its long shelf life made it a staple during wartime and an export for nations like Brazil and New Zealand. Canned corned beef remains widely used in places such as the Philippines, the Caribbean, and West Africa, where it is incorporated into local dishes.

Why People Think It Has Corn

Despite its true origin, the misconception that corned beef involves corn persists today.

Language Confusion

The confusion stems from the evolution of the word “corn.” In Old English, “corn” referred to any grain or particle, including salt or barley. Over time, American English narrowed “corn” to mean maize. As a result, modern English speakers naturally associate the word with the yellow vegetable rather than salt.

Cultural Associations

In the United States, the dish became strongly linked to St. Patrick’s Day, Irish heritage, and hearty home cooking. Because few people learn about the preservation process behind the name, many assume it includes corn or corn-fed beef. Popular culture reinforces the mix-up, as few menus or labels explain the historical meaning of “corned.”

Production Has Changed

Today’s corned beef often uses a liquid brine rather than coarse salt crystals. Because the salt is no longer visible, the name’s original meaning is less obvious. This makes it easier to mistake “corned” for a flavoring rather than a curing method.

What Corned Beef Actually Is

Understanding what corned beef truly is helps explain its texture, flavor, and cultural importance.

The Meat and the Method

Corned beef is usually made from beef brisket, a tough cut that benefits from long, slow cooking. The meat is soaked in a brine of water, salt, sugar, nitrates, and spices for several days. This process tenderizes the beef, preserves it, and gives it its characteristic pink color.

Cooking methods vary, but simmering or slow-cooking the beef until tender is the most common approach. The result is flavorful, juicy meat that pairs well with potatoes, cabbage, and mustard.

Nutrition and Moderation

Corned beef provides protein, iron, and zinc, but also contains high levels of sodium due to the curing process. Health experts suggest enjoying it occasionally rather than frequently, especially for those watching salt intake.

Cultural Significance

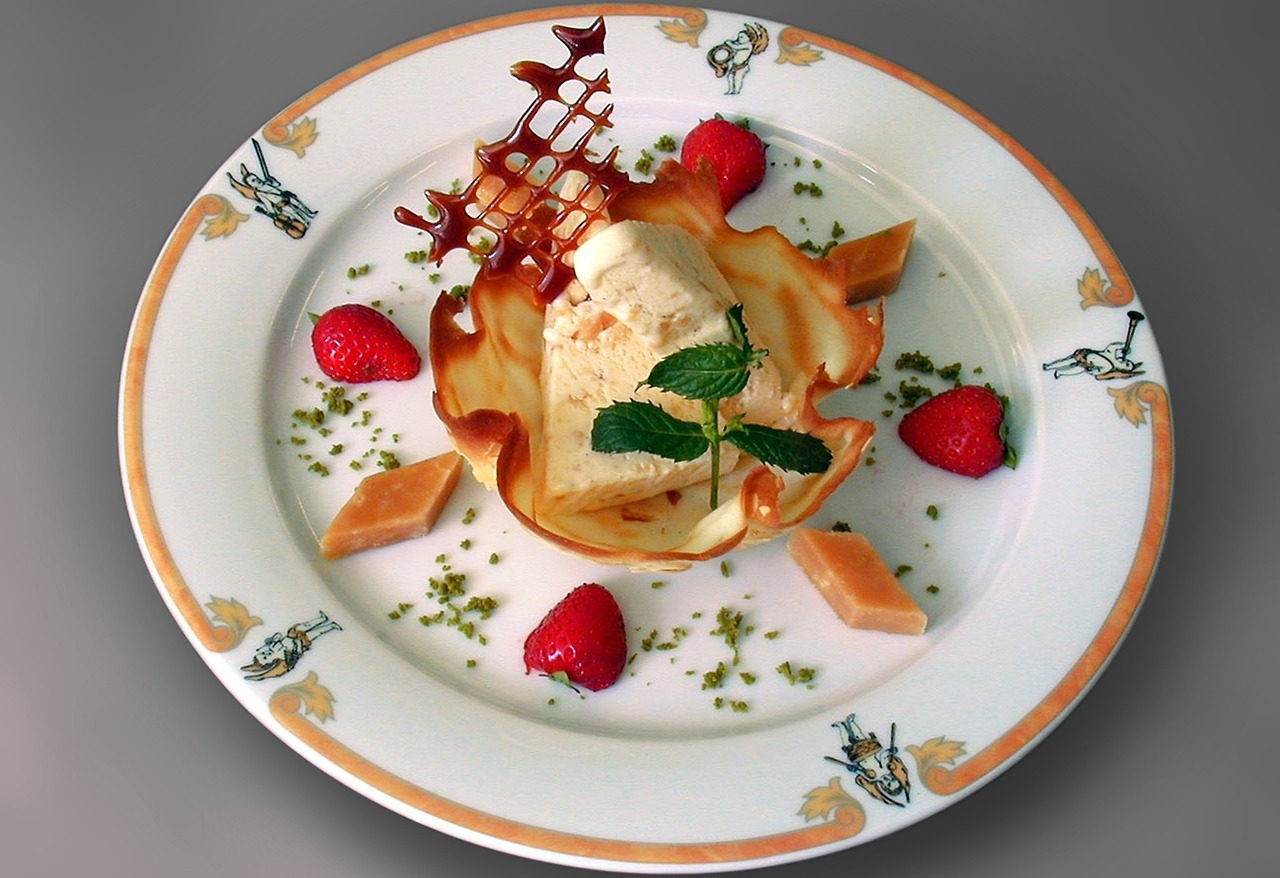

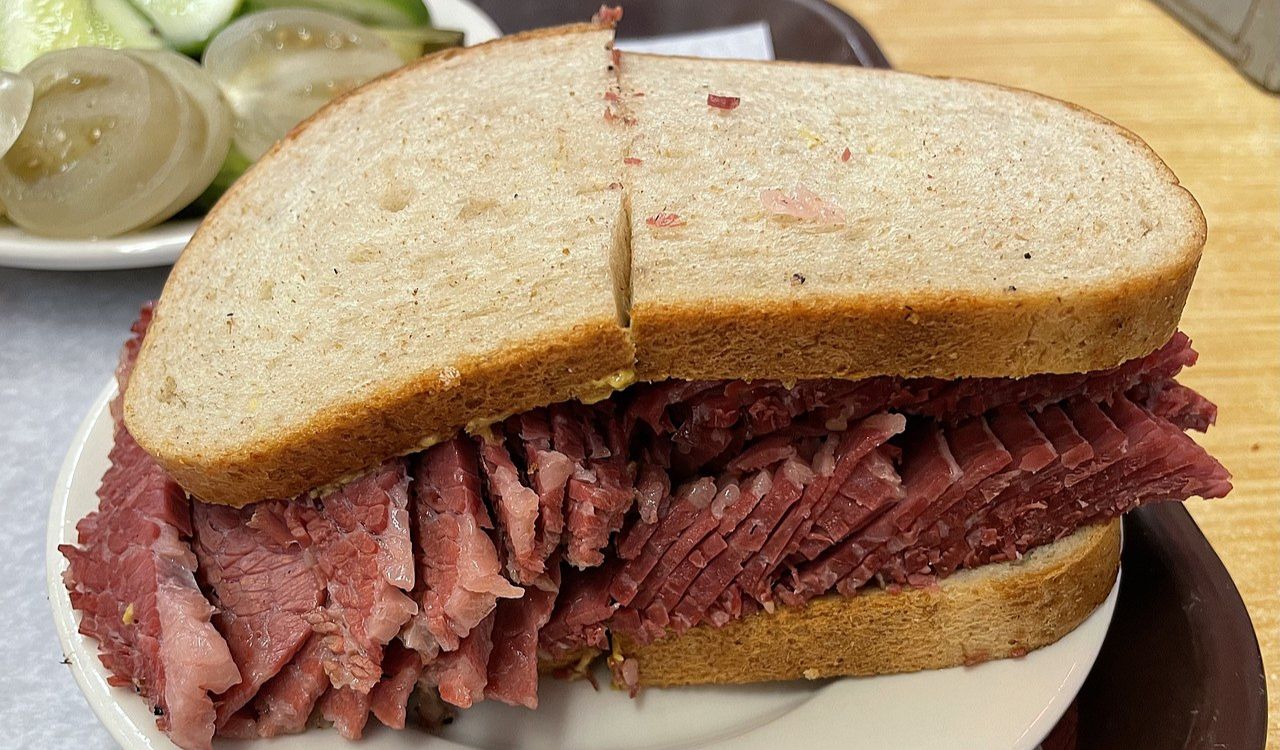

In Jewish delis, corned beef became a key ingredient in sandwiches such as the Reuben. It shares roots with pastrami, which is cured in a similar way but smoked afterward. In Irish-American households, boiled corned beef with cabbage remains a beloved tradition, even though it is not a native Irish dish.

Understanding the origin of the name adds depth to these meals, connecting modern cooking to centuries of preservation and migration.

Tips for Cooking and Buying Corned Beef

When choosing or preparing corned beef, consider these simple tips for best results:

- Choose the right cut. Brisket remains the traditional choice because it becomes tender with slow cooking.

- Rinse before cooking. Briefly rinse store-bought corned beef to remove excess salt from the brine.

- Cook it low and slow. Simmer gently for several hours or use a slow cooker to achieve perfect tenderness.

- Add vegetables late. Potatoes, carrots, and cabbage should go in near the end to prevent overcooking.

- Slice against the grain. Cutting the beef across the fibers keeps each slice tender and easy to chew.

Understanding that “corned” refers to salt curing (and not corn) will give you a better sense of why these steps matter.

The Takeaway

Corned beef has never contained corn. The “corn” in its name comes from the coarse salt grains once used to cure beef before refrigeration existed. The dish’s history stretches from Irish trade and British preservation to American holiday tables and global canned exports.

Recognizing this simple linguistic twist turns a misunderstood food into a fascinating piece of history. Every time you prepare corned beef and cabbage or order a deli sandwich, you’re tasting a dish shaped by centuries of preservation, trade, and cultural exchange.

Corned beef may no longer require those coarse “corns” of salt, but the name endures as a reminder of how food traditions evolve and how language shapes the way we understand what we eat.

References

- Column: Savory history of corned beef in America- YouAreCurrent.com

- The History of Corned Beef- KitchenProject.com

- Corned Beef and Food Safety- FSIS.USDA.gov

- How Did Corned Beef Get Its Name?- TastingTable.com